Business Process Transformation

Definition and background

In contrast to the traditional functional work division where each department has its own specific duties, in the process-oriented division of work, each department has its own products/services. In traditional organisations, a single customer inquiry passes through many departments to be met, whereas in process-oriented organisations it is possible for a customer enquiry to be accomplished from start to the very end within one single department. Figure 1 demonstrates the difference between process orientation and functional orientation. Circles represent the organisation, and shapes inside the circles represent people working together. In the first circle we see some people who are working individually. Each of them does exactly the same work as other people, and produces the same products; e.g. each makes a whole shoe individually. Then the “Division of Work” comes and each person undertakes a different role, e.g. one brings the leather, another one cuts it, etc. In this situation, people together make products, and meet the customer enquiries very efficiently. Then the team expands and people with the same function come together in departments (No. 3), e.g. one department provides leather, another department cuts them, etc. This function-based organisation has its own problems such as lack of agility and lack of responsibility toward the customer expected outcomes.

Figure 1. Difference between process orientation and Functional Orientation

Process orientation (No. 4) suggests a different departmentation where each department has its own set of products, e.g. one department produces women shoes, another one produces men shoes, etc. Although the process-oriented situation (No. 4) has been evidenced to be more efficient, when the organisation naturally falls into the functional orientation trap, it becomes very difficult to get out.

Porter (1985) was maybe the first person who suggested that companies should “reorder” or “regroup” their “value-adding activities” in order to achieve dramatic improvements in their performance. Hammer (1990) and Davenport and Short (1990) used the word “processes” instead of value activities and suggested that firms should use the power of modern information technology to radically “redesign” or “reengineer” their business processes. That was tantamount to a revolution in the organisation, destroying the existing systems and procedures. Many companies followed Hammer’s call and launched BPR projects but that was when the implementation problems became evident. Many reengineering projects failed to conquer structural inertia to implement that fundamental change. There were even reports that 60-80 percent of BPR projects failed. On the basis of the high failure rate, some authors concluded that BPR was just a management fashion, or that it was a good theoretical idea that was impractical to implement. However, the idea of obliteration of non-value added functions was still a logical way to proceed with innovation.

Some other researchers stated that being unappreciative of human dimension and obliteration of the current structure are the main problems with the BPR. They suggested that process orientation should happen in a gradual manner rather than a thorough reengineering. For example, it was suggested that after definition of the new structure, the old structure should remain in place, and fade out gradually over a long period of time. Some others suggested that instead of a revolutionary change, people should be prepared for a long period of time, and practice the change before it actually happens in one pre-planned day (Big-Bang). Parallel and relay methods were also suggested as other options for gradual process orientation. To highlight the difference of their suggested methods to BPR, authors used Business Process Management (BPM) as the name of the new methodology.

During the last decade, related books and articles have been published mostly under the name of process management instead of reengineering; however, BPM has remained in the fad phase and researchers are still uncertain about the substantive meaning of process management and how it should be used.

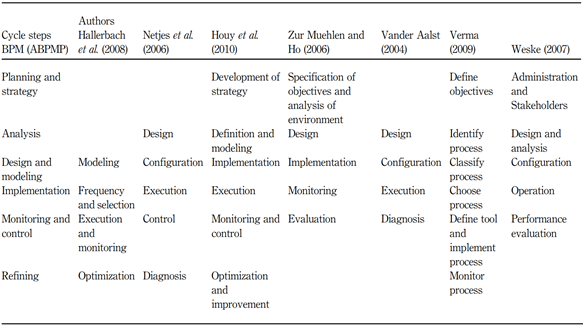

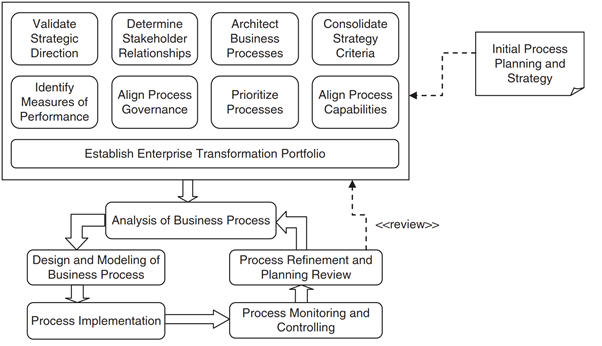

To investigate the BPM lifecycle models within the academic-scientific ambit, de Morais et al. (2014) conducted a literature review, and found seven BPM models. They analyzed those models, and compared them with the BPM model presented by the Association of Business Process Management Professionals (2009) as presented in Table 1. Arguing that none of the studied methodologies can guarantee an alignment between strategy and business processes in organisations, de Morais et al. (2014) proposed a new BPM lifecycle as shown in Figure 2.

Porter (1985) was maybe the first person who suggested that companies should “reorder” or “regroup” their “value-adding activities” in order to achieve dramatic improvements in their performance. Hammer (1990) and Davenport and Short (1990) used the word “processes” instead of value activities and suggested that firms should use the power of modern information technology to radically “redesign” or “reengineer” their business processes. That was tantamount to a revolution in the organisation, destroying the existing systems and procedures. Many companies followed Hammer’s call and launched BPR projects but that was when the implementation problems became evident. Many reengineering projects failed to conquer structural inertia to implement that fundamental change. There were even reports that 60-80 percent of BPR projects failed. On the basis of the high failure rate, some authors concluded that BPR was just a management fashion, or that it was a good theoretical idea that was impractical to implement. However, the idea of obliteration of non-value added functions was still a logical way to proceed with innovation.

Some other researchers stated that being unappreciative of human dimension and obliteration of the current structure are the main problems with the BPR. They suggested that process orientation should happen in a gradual manner rather than a thorough reengineering. For example, it was suggested that after definition of the new structure, the old structure should remain in place, and fade out gradually over a long period of time. Some others suggested that instead of a revolutionary change, people should be prepared for a long period of time, and practice the change before it actually happens in one pre-planned day (Big-Bang). Parallel and relay methods were also suggested as other options for gradual process orientation. To highlight the difference of their suggested methods to BPR, authors used Business Process Management (BPM) as the name of the new methodology.

During the last decade, related books and articles have been published mostly under the name of process management instead of reengineering; however, BPM has remained in the fad phase and researchers are still uncertain about the substantive meaning of process management and how it should be used.

To investigate the BPM lifecycle models within the academic-scientific ambit, de Morais et al. (2014) conducted a literature review, and found seven BPM models. They analyzed those models, and compared them with the BPM model presented by the Association of Business Process Management Professionals (2009) as presented in Table 1. Arguing that none of the studied methodologies can guarantee an alignment between strategy and business processes in organisations, de Morais et al. (2014) proposed a new BPM lifecycle as shown in Figure 2.

Table 1. The BPM lifecycle models studied by de Morais et al. (2014)

Figure 2. BPM framework proposed by de Morais et al. (2014) emphasising on strategy

BPR has also been always popular within academia and industry, and there are many authors who are interested in BPR methodologies. The difference between BPM and BPR methodologies is that in most cases, BPR authors have a project focus, whereas in BPM, authors are mostly interested in the processes lifecycle. As BPR writers have a narrower focus, they consider the BPR project in more depth. Although BPR writers have a more in-depth view, they do not provide a guideline on how to design the new process structure to reduce the risk of failure in the process orientation.

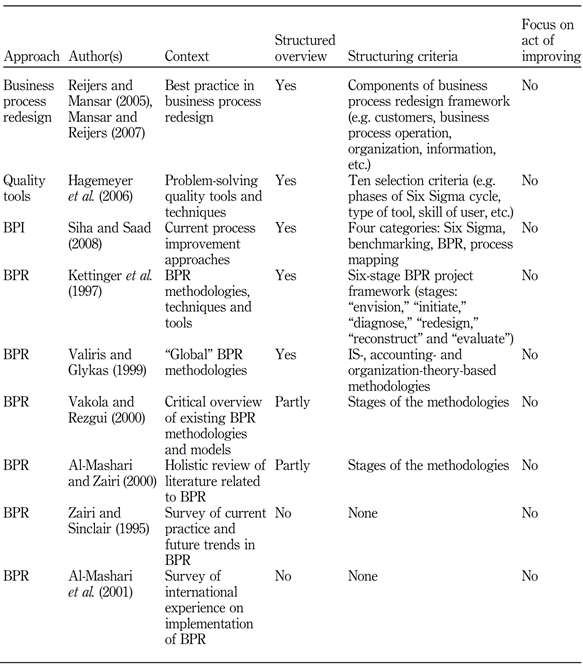

In a literature review, Zellner reviewed the process improvement methodologies published in EBSCO and Emerald databases (Table II), and could not find any methodology focussing on the “act of improving” or in other words, the “redesign stage.” This gap in the literature has still remained unchanged. As an example, Eftekhari and Akhavan (2013) who propose an IT tools-based BPR methodology (CITM) in order to facilitate these projects, only recommend benchmarking and considering the current status of the processes in the “modifying and redesigning” stage.

There are two main facts in the existing BPM and BPR methodologies. The first fact is that although the number of steps and terminologies used varies significantly, cycle steps do not present fundamental differences and are only divided differently. The second fact is that those BPM models mostly aim to provide a comprehensive view on all of the main activities involved in process management and strategic alignment, with insignificant focus on mitigating the risk of failure in their redesign stage.

In a research article on Process Focussed Organisations features and characteristics, Neubauer (2009) made a survey within Austrian companies. His survey showed that only 6 percent of the participating organisations stated their business processes as completely aligned with their business strategy. This low figure indicates how difficult is to achieve process orientation in reality. Although the idea of obliteration of out-dated non-value-adding processes is too powerful to ignore, a 6 percent success rate is very discouraging.

In a literature review, Zellner reviewed the process improvement methodologies published in EBSCO and Emerald databases (Table II), and could not find any methodology focussing on the “act of improving” or in other words, the “redesign stage.” This gap in the literature has still remained unchanged. As an example, Eftekhari and Akhavan (2013) who propose an IT tools-based BPR methodology (CITM) in order to facilitate these projects, only recommend benchmarking and considering the current status of the processes in the “modifying and redesigning” stage.

There are two main facts in the existing BPM and BPR methodologies. The first fact is that although the number of steps and terminologies used varies significantly, cycle steps do not present fundamental differences and are only divided differently. The second fact is that those BPM models mostly aim to provide a comprehensive view on all of the main activities involved in process management and strategic alignment, with insignificant focus on mitigating the risk of failure in their redesign stage.

In a research article on Process Focussed Organisations features and characteristics, Neubauer (2009) made a survey within Austrian companies. His survey showed that only 6 percent of the participating organisations stated their business processes as completely aligned with their business strategy. This low figure indicates how difficult is to achieve process orientation in reality. Although the idea of obliteration of out-dated non-value-adding processes is too powerful to ignore, a 6 percent success rate is very discouraging.

Table 2. Summary of the process improvement methodologies studied by Zelner (2014)

Many of the failures associated with process orientation can be attributed to a neglect of the concerns of employees and their resistance to radical change. Acknowledging people connections and minimizing the impact of our process redesign on them and their belongings can minimize the risk of failure in process orientation. Click here to see how it is possible to change from a function-based structure to a process-based structure without changing the existing structure in 7 steps.