Steps in BPR2

To reduce the employees’ resistance to change, and achieve a process-oriented framework without destroying the existing structure, BPR2 suggests the following seven steps:

The following sections provide a detailed description on the above steps.

- aiming for excellence;

- definition of internal and external customer values;

- rearrangement to ensure customer values;

- creating new customer values;

- renaming to promote customer values;

- automation to facilitate customer values; and

- measurement of customer values.

The following sections provide a detailed description on the above steps.

Step 1: aiming for excellence

The first step in BPR2 is to determine and communicate what is expected from BPR2. How the leaders induce and explain the reason of change to their staff is very important for the success of the change imposed. The survey conducted by Terziovski et al. (2003) shows that an organisation is more likely to achieve greater profitability if the process re-engineering is implemented in a proactive manner as part of an organisation’s business strategy. Their results show that organisations that implement BPR reactively as a “quick fix” do not achieve significant performance outcomes.

As a proactive manner, it is suggested for the BPR2 project to be executed within a suit of projects that aim for Business Excellence (BE). Aims such as cost reduction, redundancy or even increasing the profitability may result in employees’ resistance and failure. BE models are diagnostic tools which allow companies to assess how they are managing all key areas of their businesses and the quality of the results they are achieving. BE models such as the Malcolm Baldrige Model or the model presented by the European Foundation for Quality Management (EFQM) recommend many strategies for a sustainable improvement including the process orientation. Thus, training the employees on the BE principles can help them to understand the benefits of process orientation, and reduce their resistance.

Step 2: definition of internal and external customer values

The second step in BPR2 is to identify what is valuable for the internal/external customers. This step consists of four main activities including: first, recognition of the current and potential internal/external customers (according to the vision and strategies); second, detailed recognition of their characteristics; third, clear recognition of their needs, wants, and expectations; and fourth, deciding about what valuable products the organisation is going to offer to each group of customers in return to what is expected from them.

What is referred to as “customer value” in this thesis appears also in management literature as “consumer value,” and appears in the marketing literature as the “marketing mix.” Customer value can be defined as a set of benefits and attributes in a property, product or service that persuades a customer to pay the price, take possession of it, and enjoy taking benefit from it.

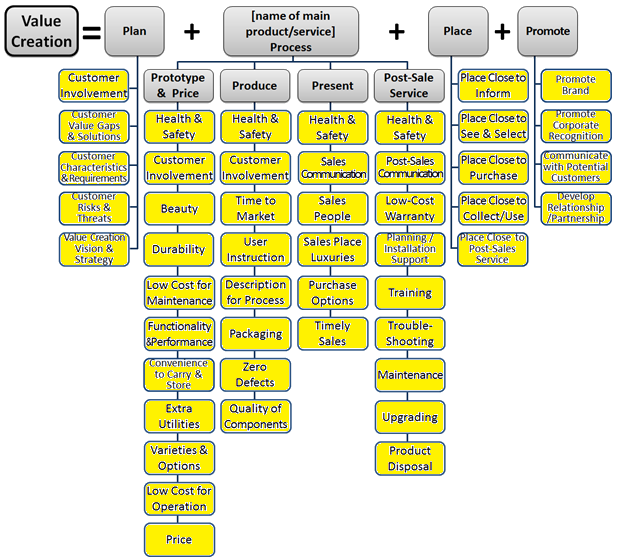

For its purposes, this study presents a comprehensive customer value model from an authoritative view shown in the below figure as the “P8 Model.” In this customer value or marketing mix model, eight processes are defined as plan, prototype, price, produce, present, post-sale service, place, and promote. Each of these processes provides a distinct value for customer. All of the P’s defined here have equivalents in other marketing mix models except for the “Plan” which has not usually been included as a part of marketing mix. In many businesses, the customer requires help to decide on the suitable product/service/solution, and such a help is valuable for him/her. A patient who pays a doctor for prescribing the diagnostic tests (X-ray, blood test, etc.), or a business owner who pays a management consultant for a business review and prioritizing improvement projects, or an investor who recruits a financial adviser for future investments are examples of when “Planning” comes before the main product/ service. After this planning phase, most customers prefer to purchase the planned solution from the same provider. Thus, considering “Planning” as an extra element in marketing mix may help businesses in their marketing efforts.

The outcome of the customer value definition step is the identification of all of the current and future internal/external customer groups, and customized P8-plots for each of the products/services for each group of the relevant customers. The BPR consultants use brainstorming in definition of new processes; whereas in BPR2, P8 Model enables process designers to define processes (grey boxes in the below figure) for each group of stakeholders in a precise and comprehensive manner. The next step will describe why and how processes on these P8-Plots should be assigned to the current departments and their sub-groups to ensure expected customer values.

Step 3: rearrangement to ensure customer values

The third step in BPR2 is rearranging the current departments’ responsibilities in a way that each department undertakes the whole responsibility of certain processes on the customised P8-plots for certain group(s) of internal/external customers. This is a major step that provides a practical pathway to turn the traditional functional structure into a process-based structure maintaining the current structure and work groups.

A deputy president in a milk processing firm narrated a case that can best explain what is meant in this thesis as the process rearrangement. He said that many years ago, they used to pack produced cheese in large metal cans, and this made the cheese sensitive to the storage temperature. Some retailers did not store them in fridges as instructed by the company, and this resulted in early spoiling of the cheese. Consumers became poisoned every now and then, and sued the company. Finally, the deputy president ordered the production manager to take the whole responsibility of the cheese from the time milk is purchased, until retailers sold it to end customers. The production manager was reluctant to accept such a responsibility as he believed that retailers, who were to be blamed in that matter, would not follow the procedures anyway. However, under the obligation from the deputy president, the production manager took the responsibility, and solved the problem.

The first step in BPR2 is to determine and communicate what is expected from BPR2. How the leaders induce and explain the reason of change to their staff is very important for the success of the change imposed. The survey conducted by Terziovski et al. (2003) shows that an organisation is more likely to achieve greater profitability if the process re-engineering is implemented in a proactive manner as part of an organisation’s business strategy. Their results show that organisations that implement BPR reactively as a “quick fix” do not achieve significant performance outcomes.

As a proactive manner, it is suggested for the BPR2 project to be executed within a suit of projects that aim for Business Excellence (BE). Aims such as cost reduction, redundancy or even increasing the profitability may result in employees’ resistance and failure. BE models are diagnostic tools which allow companies to assess how they are managing all key areas of their businesses and the quality of the results they are achieving. BE models such as the Malcolm Baldrige Model or the model presented by the European Foundation for Quality Management (EFQM) recommend many strategies for a sustainable improvement including the process orientation. Thus, training the employees on the BE principles can help them to understand the benefits of process orientation, and reduce their resistance.

Step 2: definition of internal and external customer values

The second step in BPR2 is to identify what is valuable for the internal/external customers. This step consists of four main activities including: first, recognition of the current and potential internal/external customers (according to the vision and strategies); second, detailed recognition of their characteristics; third, clear recognition of their needs, wants, and expectations; and fourth, deciding about what valuable products the organisation is going to offer to each group of customers in return to what is expected from them.

What is referred to as “customer value” in this thesis appears also in management literature as “consumer value,” and appears in the marketing literature as the “marketing mix.” Customer value can be defined as a set of benefits and attributes in a property, product or service that persuades a customer to pay the price, take possession of it, and enjoy taking benefit from it.

For its purposes, this study presents a comprehensive customer value model from an authoritative view shown in the below figure as the “P8 Model.” In this customer value or marketing mix model, eight processes are defined as plan, prototype, price, produce, present, post-sale service, place, and promote. Each of these processes provides a distinct value for customer. All of the P’s defined here have equivalents in other marketing mix models except for the “Plan” which has not usually been included as a part of marketing mix. In many businesses, the customer requires help to decide on the suitable product/service/solution, and such a help is valuable for him/her. A patient who pays a doctor for prescribing the diagnostic tests (X-ray, blood test, etc.), or a business owner who pays a management consultant for a business review and prioritizing improvement projects, or an investor who recruits a financial adviser for future investments are examples of when “Planning” comes before the main product/ service. After this planning phase, most customers prefer to purchase the planned solution from the same provider. Thus, considering “Planning” as an extra element in marketing mix may help businesses in their marketing efforts.

The outcome of the customer value definition step is the identification of all of the current and future internal/external customer groups, and customized P8-plots for each of the products/services for each group of the relevant customers. The BPR consultants use brainstorming in definition of new processes; whereas in BPR2, P8 Model enables process designers to define processes (grey boxes in the below figure) for each group of stakeholders in a precise and comprehensive manner. The next step will describe why and how processes on these P8-Plots should be assigned to the current departments and their sub-groups to ensure expected customer values.

Step 3: rearrangement to ensure customer values

The third step in BPR2 is rearranging the current departments’ responsibilities in a way that each department undertakes the whole responsibility of certain processes on the customised P8-plots for certain group(s) of internal/external customers. This is a major step that provides a practical pathway to turn the traditional functional structure into a process-based structure maintaining the current structure and work groups.

A deputy president in a milk processing firm narrated a case that can best explain what is meant in this thesis as the process rearrangement. He said that many years ago, they used to pack produced cheese in large metal cans, and this made the cheese sensitive to the storage temperature. Some retailers did not store them in fridges as instructed by the company, and this resulted in early spoiling of the cheese. Consumers became poisoned every now and then, and sued the company. Finally, the deputy president ordered the production manager to take the whole responsibility of the cheese from the time milk is purchased, until retailers sold it to end customers. The production manager was reluctant to accept such a responsibility as he believed that retailers, who were to be blamed in that matter, would not follow the procedures anyway. However, under the obligation from the deputy president, the production manager took the responsibility, and solved the problem.

P8 Model for Customer-Value and Marketing Mix

As discussed earlier, each grey box in the P8-plot represents a process or subprocess. Consequently, immediately after a manager takes the responsibility of a relevant process (grey box) for a product/service for a group of internal/external customer, the position becomes process oriented. Rearrangements should take place with ideally no change in managerial levels and their subordinate teams, and with minimal change in their working places. It is possible for a manager to take the responsibility of more than one process, but delegation of authority of one process in one geographical region/market to more than one manager is not recommended. More senior managers should take the responsibility of one or more processes for a larger group of products/services or larger groups of customers.

BPR2 changes the departmental boundaries, but does not consider people as components that can be easily moved or removed from the organisation. In contrast to BPR that holds little concern for the organisation’s existing human resources, BPR2 does not separate people from their current teams. After a BPR2, the organisational structure will remain unchanged with new roles for departments to play.

Step 4: creating new customer values

After giving the whole responsibility of end-to-end processes to the existing departments, departments that used to provide support for production department such as procurement and quality control departments may have no product/service to provide. The fourth step in BPR2 is to define a new role for those departments. It is strongly recommended that in this situation, leaders should think creatively and regard it as an opportunity to create new products/services rather than removing the extra departments from their organisation. For example, the quality control department can start a quality management consultancy business, and the procurement department can start a foreign trade business and so on.

Hammer (1990) clearly described how Ford’s account payable department achieved 75 percent reduction in head count by undertaking a BPR project. However, there was no explanation in his article on what happened to those people who were cut, and the ones who survived. Staff layoffs damage firm’s reputation, and provoke guilt and remorse and loss of trust, commitment, and productivity in surviving employees, and cause disruption and disorder. According to Drago and Geisler (1997):

Companies which have undergone BPR tend to experience several indicators of low morale, such as growing unwillingness to work longer hours and increases in absenteeism. There is a sense of loss and uncertainty due to downsizing and the lack of knowledge as to what to expect. Low morale tends to disrupt the flow of ideas, to interfere with sharing of information, and to hinder teamwork. Fear and suspicion tend to replace trust and attitudes that welcome challenge and discovery.

BPR2 suggests that the business leaders should regard their departments as business units with the potential of production and independent income. This new approach enables the leaders to consider all of the opportunities for starting new businesses in their current departments. In traditional business models, all of the people in the firm work for one business, and the people who are found unable to contribute in that business, get sacked. For example, in a car manufacturing company, everyone is focussed on car marketing, manufacturing and sales; and no one considers other investments and incomes. By putting all of the eggs in one basket, when that main business fails, the whole company goes bankrupt.

Creating value and wealth is not limited to the production or service departments, and other departments on their own can contribute to the profit. Many people and businesses have created a fortune just through fruitful investments and effective cash flows; many entrepreneurs and businesses create wealth by producing and selling businesses and brands; many businesses earn their income by creating and selling patents. Likewise, HR Department can provide recruitment services for other companies; Finance Department can provide consultancy and fruitful cash flows for shareholders and other companies; and sales department can also produce and sell new brands. Taking this view, redundancies are not the best option, and entrepreneurship and growth should come first.

When this thesis talks about developing new businesses, it does not mean that one large business should be converted to many small businesses. To ensure sustainability, the business in which the company has a competitive advantage, should remain in focus like the main pole of a tent. Departments should support the main business, and at the same time think more creatively, and extend their view beyond their tangible assets and organisational borders. Departments are recommended to start communicating with other people and businesses on the other side of the fence, and contribute to the innovation and wealth.

After rearrangement of responsibilities, the current names of departments and sub-groups may no more be applicable. The following section will describe why and how department names can be changed to reflect their main products/services, and improvements that they are going to make according to the strategies.

Step 5: renaming to promote customer values

Taking benefit from the power of name is the fifth step in BPR2. Searching the “power of names” exact phrase over the internet produces 273,000 results (viewed August 13, 2013). There seems to be a widespread consensus about the importance of name. In academic papers many authors have mentioned the impact of name on the firm value (Mase, 2009; Berkman et al., 2011), on employability (Guéguen and Pascual, 2012), on health care (Burt, 2011), and even on the presidential election (Block and Onwunli, 2010).

With such a strong consensus on the power of name, there seems to be a gap in the literature on how to name departments or business processes to make a better impact on employees and other stakeholders. Name is the most communicated characteristic of a department; however, this most communicated characteristic of the departments has always been the most neglected characteristic as well. We name departments by their main activity, and not by their valuable product. Department names such as engineering, procurement, documentation, accounting, and finance seem to be very normal; however, the problem arises when people forget about the value they really need to create for their customers. For example, “Engineering Department” or R&D are very common names in industries and generally refer to the department in which design and making samples of new products take place. However in most cases, R&D and engineering departments are involved in non-creative and routine works such as regular samplings and testings and whatever duties that has no one else in charge.

If we change R&D or “Engineering Department” to “Innovators Department,” their staff will be more likely to focus on creativity and innovation. It will also attract a better support from company leaders, and the department will remember to employ innovative staff rather than just engineers/researchers. The main idea in the process renaming is that in contrast to the brand names that should be short and attractive, department names should be prestigious, exciting and informative. Department names are appellative and do not need to have the characteristics of proper names. For a process, a descriptive epithet highlighting the valuable product of the process, makes a clearer sense and better impact. As the name of a department is the most communicated property of it, choosing a name that reflects the expected customer values, can promote values in everyday activities and communications.

As an example, finance departments are expected to provide wealth and financial information for shareholders; however, when we look for an information document in simple words understandable for the shareholders who may know nothing about accountancy, in many cases we may come to an absolute zero. Finance departments mostly focus on controlling the capitals, and have no temptation to look for other opportunities for investment and increasing the profit for shareholders. Changing the name of Finance Department to “Shareholder Advisors and Wealth Creators” would remind them the valuable products they need to provide for their shareholders.

In contrast to what is recommended in this thesis as naming the processes by their valuable products, Hammer and Champy (1993) briefly suggest that process names that express their beginning and end states, enable better handling of the processes. They, e.g. suggest that manufacturing is better called the procurement-to-shipment process. Hammer and Champy do not provide any more explanation or further reasoning for such a renaming.

Burt (2011) is one of the few authors who examine the impact of name change on both staffs and customers. Burt suggests changing the name of “Palliative Care” in hospitals to “Supportive Care” as an “effective approach to improving perceptions of the service – particularly for patients.” Palliative care aims to alleviate symptoms of illnesses that affect patients mostly at the last stages of their life, to improve their quality of life within the limitations of the condition. This name change is still referring the department by its main activity (supportive care), and not by their valuable product (improved quality of life). Thus not surprisingly, Burt (2011) admits that although the majority of care professionals supported it as they perceived the patients preferred it, this name change had no impact on their referral patterns. Instead of changing the name to “Supportive Care,” BPR2 suggests the name change of “Palliative Care” in hospitals to “Quality of Life Improvers.” Such a name change might make a more positive impression on professionals, and ignite creative solutions to provide a more satisfactory life for the patients with life-ending illnesses. It can be also suggested that if there is no conventional cure for palliative people, why not to try unconventional and creative cures? In that case, “Palliative Care” can be also renamed to “Creative Life Improvers.”

Step 6: automation to facilitate customer values

The sixth step in BPR2 is to provide a solution for the overloaded departments. After rearrangement of responsibilities, some departments may lose the support they used to receive from other departments (e.g. from procurement department) and encounter an increase in work load. The solution recommended in this step is to take a few volunteer people from other departments or preferably take benefits from the internet capacities or other available automation technologies. Information technology has enabled us to better manage data, information and knowledge, and reduce barriers of time, place and language. However, any effort for a costly automation or technology change should be provided with sufficient explanation and reasoning in terms of its impact on the products/services it provides for the internal/external with facts and figures. At this stage, as the P8-plots have enabled departments to exactly comprehend the customer values they are responsible for, they can better decide on the of use information technology or any other types of technologies to cope with the new situation and increase the value of their products/services for their customers.

In BPR2, automation comes after the process rearrangements, and this is in agreement with the authors such as Gargeya and Brady (2005) who recommend the process redesign prior to adoption of SAP in ERP systems. In contrast to Hammer and Champy (1993) who suggest the information technology as an essential enabler and a crucial part of the process reengineering (BPR), implementation of BPR2 is not dependent to the information technology. Mixing IT with process orientation, as we can see in some process integration systems, brings the problems of inflexibility and rigidity if the software does not fit the future firm (Lindley et al., 2008). By using the P8-plots, BPR2 determines the processes, and then managers can decide on compare different options and tools and technologies to optimise the whole value for their customers. By separating the information technology from the process thinking, BPR2 makes the process orientation easier and more affordable for any size and any type of industry.

Step 7: measurement of customer values

The last step in BPR2 is definition of process measures and targets according to the P8-plots and strategic goals and objectives. White boxes in P8-plots provide the measurement criteria, and the strategic goals provide targets. Measurements are recommended to be conducted continuously and include efficiency (consumption of time, money […]) and effectiveness (customer perceptions and other desired outcomes).

Regular top managers’ review sessions are recommended to be monthly reviewing the assessment results compared to targets and benchmarks, and suggestions for improvement of the customer values, process arrangements, and names. At this stage, there would be process-oriented departments in place that would easily accept any change in responsibilities and products. The cycle begins again with the definition of internal and external customer values, and will continue in a much easier manner.

BPR2 changes the departmental boundaries, but does not consider people as components that can be easily moved or removed from the organisation. In contrast to BPR that holds little concern for the organisation’s existing human resources, BPR2 does not separate people from their current teams. After a BPR2, the organisational structure will remain unchanged with new roles for departments to play.

Step 4: creating new customer values

After giving the whole responsibility of end-to-end processes to the existing departments, departments that used to provide support for production department such as procurement and quality control departments may have no product/service to provide. The fourth step in BPR2 is to define a new role for those departments. It is strongly recommended that in this situation, leaders should think creatively and regard it as an opportunity to create new products/services rather than removing the extra departments from their organisation. For example, the quality control department can start a quality management consultancy business, and the procurement department can start a foreign trade business and so on.

Hammer (1990) clearly described how Ford’s account payable department achieved 75 percent reduction in head count by undertaking a BPR project. However, there was no explanation in his article on what happened to those people who were cut, and the ones who survived. Staff layoffs damage firm’s reputation, and provoke guilt and remorse and loss of trust, commitment, and productivity in surviving employees, and cause disruption and disorder. According to Drago and Geisler (1997):

Companies which have undergone BPR tend to experience several indicators of low morale, such as growing unwillingness to work longer hours and increases in absenteeism. There is a sense of loss and uncertainty due to downsizing and the lack of knowledge as to what to expect. Low morale tends to disrupt the flow of ideas, to interfere with sharing of information, and to hinder teamwork. Fear and suspicion tend to replace trust and attitudes that welcome challenge and discovery.

BPR2 suggests that the business leaders should regard their departments as business units with the potential of production and independent income. This new approach enables the leaders to consider all of the opportunities for starting new businesses in their current departments. In traditional business models, all of the people in the firm work for one business, and the people who are found unable to contribute in that business, get sacked. For example, in a car manufacturing company, everyone is focussed on car marketing, manufacturing and sales; and no one considers other investments and incomes. By putting all of the eggs in one basket, when that main business fails, the whole company goes bankrupt.

Creating value and wealth is not limited to the production or service departments, and other departments on their own can contribute to the profit. Many people and businesses have created a fortune just through fruitful investments and effective cash flows; many entrepreneurs and businesses create wealth by producing and selling businesses and brands; many businesses earn their income by creating and selling patents. Likewise, HR Department can provide recruitment services for other companies; Finance Department can provide consultancy and fruitful cash flows for shareholders and other companies; and sales department can also produce and sell new brands. Taking this view, redundancies are not the best option, and entrepreneurship and growth should come first.

When this thesis talks about developing new businesses, it does not mean that one large business should be converted to many small businesses. To ensure sustainability, the business in which the company has a competitive advantage, should remain in focus like the main pole of a tent. Departments should support the main business, and at the same time think more creatively, and extend their view beyond their tangible assets and organisational borders. Departments are recommended to start communicating with other people and businesses on the other side of the fence, and contribute to the innovation and wealth.

After rearrangement of responsibilities, the current names of departments and sub-groups may no more be applicable. The following section will describe why and how department names can be changed to reflect their main products/services, and improvements that they are going to make according to the strategies.

Step 5: renaming to promote customer values

Taking benefit from the power of name is the fifth step in BPR2. Searching the “power of names” exact phrase over the internet produces 273,000 results (viewed August 13, 2013). There seems to be a widespread consensus about the importance of name. In academic papers many authors have mentioned the impact of name on the firm value (Mase, 2009; Berkman et al., 2011), on employability (Guéguen and Pascual, 2012), on health care (Burt, 2011), and even on the presidential election (Block and Onwunli, 2010).

With such a strong consensus on the power of name, there seems to be a gap in the literature on how to name departments or business processes to make a better impact on employees and other stakeholders. Name is the most communicated characteristic of a department; however, this most communicated characteristic of the departments has always been the most neglected characteristic as well. We name departments by their main activity, and not by their valuable product. Department names such as engineering, procurement, documentation, accounting, and finance seem to be very normal; however, the problem arises when people forget about the value they really need to create for their customers. For example, “Engineering Department” or R&D are very common names in industries and generally refer to the department in which design and making samples of new products take place. However in most cases, R&D and engineering departments are involved in non-creative and routine works such as regular samplings and testings and whatever duties that has no one else in charge.

If we change R&D or “Engineering Department” to “Innovators Department,” their staff will be more likely to focus on creativity and innovation. It will also attract a better support from company leaders, and the department will remember to employ innovative staff rather than just engineers/researchers. The main idea in the process renaming is that in contrast to the brand names that should be short and attractive, department names should be prestigious, exciting and informative. Department names are appellative and do not need to have the characteristics of proper names. For a process, a descriptive epithet highlighting the valuable product of the process, makes a clearer sense and better impact. As the name of a department is the most communicated property of it, choosing a name that reflects the expected customer values, can promote values in everyday activities and communications.

As an example, finance departments are expected to provide wealth and financial information for shareholders; however, when we look for an information document in simple words understandable for the shareholders who may know nothing about accountancy, in many cases we may come to an absolute zero. Finance departments mostly focus on controlling the capitals, and have no temptation to look for other opportunities for investment and increasing the profit for shareholders. Changing the name of Finance Department to “Shareholder Advisors and Wealth Creators” would remind them the valuable products they need to provide for their shareholders.

In contrast to what is recommended in this thesis as naming the processes by their valuable products, Hammer and Champy (1993) briefly suggest that process names that express their beginning and end states, enable better handling of the processes. They, e.g. suggest that manufacturing is better called the procurement-to-shipment process. Hammer and Champy do not provide any more explanation or further reasoning for such a renaming.

Burt (2011) is one of the few authors who examine the impact of name change on both staffs and customers. Burt suggests changing the name of “Palliative Care” in hospitals to “Supportive Care” as an “effective approach to improving perceptions of the service – particularly for patients.” Palliative care aims to alleviate symptoms of illnesses that affect patients mostly at the last stages of their life, to improve their quality of life within the limitations of the condition. This name change is still referring the department by its main activity (supportive care), and not by their valuable product (improved quality of life). Thus not surprisingly, Burt (2011) admits that although the majority of care professionals supported it as they perceived the patients preferred it, this name change had no impact on their referral patterns. Instead of changing the name to “Supportive Care,” BPR2 suggests the name change of “Palliative Care” in hospitals to “Quality of Life Improvers.” Such a name change might make a more positive impression on professionals, and ignite creative solutions to provide a more satisfactory life for the patients with life-ending illnesses. It can be also suggested that if there is no conventional cure for palliative people, why not to try unconventional and creative cures? In that case, “Palliative Care” can be also renamed to “Creative Life Improvers.”

Step 6: automation to facilitate customer values

The sixth step in BPR2 is to provide a solution for the overloaded departments. After rearrangement of responsibilities, some departments may lose the support they used to receive from other departments (e.g. from procurement department) and encounter an increase in work load. The solution recommended in this step is to take a few volunteer people from other departments or preferably take benefits from the internet capacities or other available automation technologies. Information technology has enabled us to better manage data, information and knowledge, and reduce barriers of time, place and language. However, any effort for a costly automation or technology change should be provided with sufficient explanation and reasoning in terms of its impact on the products/services it provides for the internal/external with facts and figures. At this stage, as the P8-plots have enabled departments to exactly comprehend the customer values they are responsible for, they can better decide on the of use information technology or any other types of technologies to cope with the new situation and increase the value of their products/services for their customers.

In BPR2, automation comes after the process rearrangements, and this is in agreement with the authors such as Gargeya and Brady (2005) who recommend the process redesign prior to adoption of SAP in ERP systems. In contrast to Hammer and Champy (1993) who suggest the information technology as an essential enabler and a crucial part of the process reengineering (BPR), implementation of BPR2 is not dependent to the information technology. Mixing IT with process orientation, as we can see in some process integration systems, brings the problems of inflexibility and rigidity if the software does not fit the future firm (Lindley et al., 2008). By using the P8-plots, BPR2 determines the processes, and then managers can decide on compare different options and tools and technologies to optimise the whole value for their customers. By separating the information technology from the process thinking, BPR2 makes the process orientation easier and more affordable for any size and any type of industry.

Step 7: measurement of customer values

The last step in BPR2 is definition of process measures and targets according to the P8-plots and strategic goals and objectives. White boxes in P8-plots provide the measurement criteria, and the strategic goals provide targets. Measurements are recommended to be conducted continuously and include efficiency (consumption of time, money […]) and effectiveness (customer perceptions and other desired outcomes).

Regular top managers’ review sessions are recommended to be monthly reviewing the assessment results compared to targets and benchmarks, and suggestions for improvement of the customer values, process arrangements, and names. At this stage, there would be process-oriented departments in place that would easily accept any change in responsibilities and products. The cycle begins again with the definition of internal and external customer values, and will continue in a much easier manner.

For more info or any other inquiries, please proceed to our Contact page